The Great Kirsten Wright

The archivist I chose to interview is Kirsten Wright. Currently, Kirsten is the Program Manager with Find and Connect which is an archival project that provides history and information about Australian orphanages, children’s homes, and other institutions. Find and Connect was developed by historians, archivists, and social workers with the University of Melbourne and Australian Catholic University. They also receive the most funding from the Australian Government. Find and Connect employs an archivist because it links together different institutions’ records. Kirsten describes Find and Connect as a “giant finding aide.” Stating that “We don’t take custody of them (records), but we point to where they are and how to get access.” Find and Connect is more of a post custodial archive, rather than a collection archive since they do not house the collections. While she is not currently in a designated archivist role, Kirsten has previously worked in archival roles for the Victoria Public Records office and Victoria University archives. I asked Kirsten to speak a bit about her experiences with archival work outside of Find and Connect and if she could compare her experience working for government archives to the university archive. She stated that in the government role, she was one cog in a much bigger machine. She did her ‘part’ and the project moved to the next person in the line. At the university she was the only staff member and while she was isolated in a leaky basement, she had free reign and was able to create her own schedule. Kirsten preferred the freedom that the university archives offered. At Find and Connect, she really likes her current role and getting to work in archives without being in an archive. It lends itself to more fluid work life.

Kirsten started her career as an archivist by receiving a BA in history and politics but soon realized that she needed to add more to her resume for potential employers. During her undergrad, she had worked as a page in the school library and decided that the path of librarianship suited her well. Kirsten joined Monash University, which offered archives courses and completed her Master’s in Information Management and Systems. During her master’s program, Kirsten found archives to be far more interesting than librarianship and focused on building a career outside of book stacks.

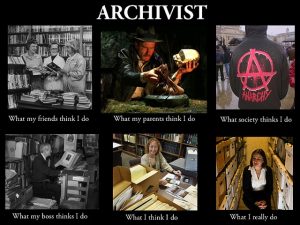

When asked how she would describe what an Archivist does she laughed a little and said that she tells people it’s “like being a librarian but you are dealing with original material that’s not held anywhere else and making it available.” Kirsten mentioned that really defining an Archivist isn’t easy! They do so many things! In her current role, she spends most of her time on managing the team, budget, and communications between their organization and the government. Right now, her team is working on redeveloping the website. So, a lot of her time is spent developing content for the developers who are completing the website. Another aspect of her role is going through emails with feedback on records. This helps to keep everything updated and accurate. Kirsten shared with me that one of the more important things she is working on right now is bringing trauma informed care into archival practice. I could tell that this was something she felt strongly about, and it meant a lot to her. So much of what Find and Connect does deals with personal information and experiences, making it important to think about how these encounters are handled. Kirsten states that “people can be traumatized by going back and getting their records.” She has found that records are often incorrect or can even have a judgmental air to them. Their job is to make the site information as accessible as possible but also a safe experience. Building a repour with the public is a big part of Kirsten’s role. Having strong communication between the institution and the people it serves helps to foster a positive connection. She stated that “relationships are so important, building up that trust and demonstrating you are a trustworthy organization.” Good communication makes sense when Find and Connect’s primary source for information are people. Kirsten thought it sounded funny to just say, “people” but they really do rely on people getting in touch with them. Find and Connect is working to add the “voices of the children” to records. Since Find and Connect are not keeping the physical records, they are one step removed from ‘issues’ that can arise is archives of not questioning the dominant narratives. The work they do provides more commentary or description around the records they keep. Kirsten likes that what she is doing incorporates the voices of the children, something she feels is lacking in a lot of older records like these. To combat any ethical hurdles, when adding personal experiences to records, Find and Connect has specific parameters for experiences and do not include abuse allegations. They also do not hold any personal information on their website, which helps to create a clear boundary. Find and Connect staff want to make sure information is available and delivered in the most ethical way for those in the community.

I asked Kirsten to speak about any other issues or challenges she has come across in archival work. She stated that “funding!” is a constant battle for any institution. Fortunately, Find and Connect was just approved for funding for the next five years. However, to combat financing issues she noted that archivists must advocate for their institution and show the value of their work. Find and Connect is working hard to make sure information is up-to-date and accessible. Community members can now count on being able to find their own records. When I asked Kirsten to think about the future of the archival profession, she quickly and frankly stated, “it’s too white and too female, at least in Australia.” Adding that the industry needs diversity, but “we need the profession to be safe for people to come in.” She couldn’t necessarily speak to America, but in Australia, there is a big problem with aboriginal peoples being discriminated against and traumatized in their profession. Aboriginal archivists and/or institutions are often shut down from doing things or required to be the expert in everything indigenous. Kirsten stated that, “so much is put onto them.” While these issues are coming to light, there is still a long way to go and structurally it is hard to see how we can make changes happen. Kirsten added that to work in a library or archive, you need a master’s degree and that can be a big barrier for most people. On a positive note, a good challenge that she sees happening is the notion that “archivists have feelings too.” She is “inspired by the work of affect, emotions and person-centered archives.” She added that while there are a lot of new technologies, she is more interested in the people.

The last question I had for Kirsten, was what her favorite thing about her job is? She smiled and explained that archives have the ability to let her do, “a bit of research and investigations.” She liked that there is a practical outcome. Kirsten added that, at least in her current role, the atmosphere is forward-thinking and progressive. She enjoys being on the side of advocacy and recognizing issues and trying to rectify them. After giving me this formal answer, Kirsten laughed and said, “and yah know, archivists are weirdos,” and that “everyone is quite interesting to work with.” I would have to agree that this profession seems to draw in creative types, myself included. Archives need people interested in histories, cultures, and expanding knowledge and resources. But they also need studious people who are patient and detail-oriented.

Kirsten was a delight to talk with and I loved being able to connect with her. Her long history of working in the archival field makes her an excellent advocate and resource!

https://www.findandconnect.gov.au/

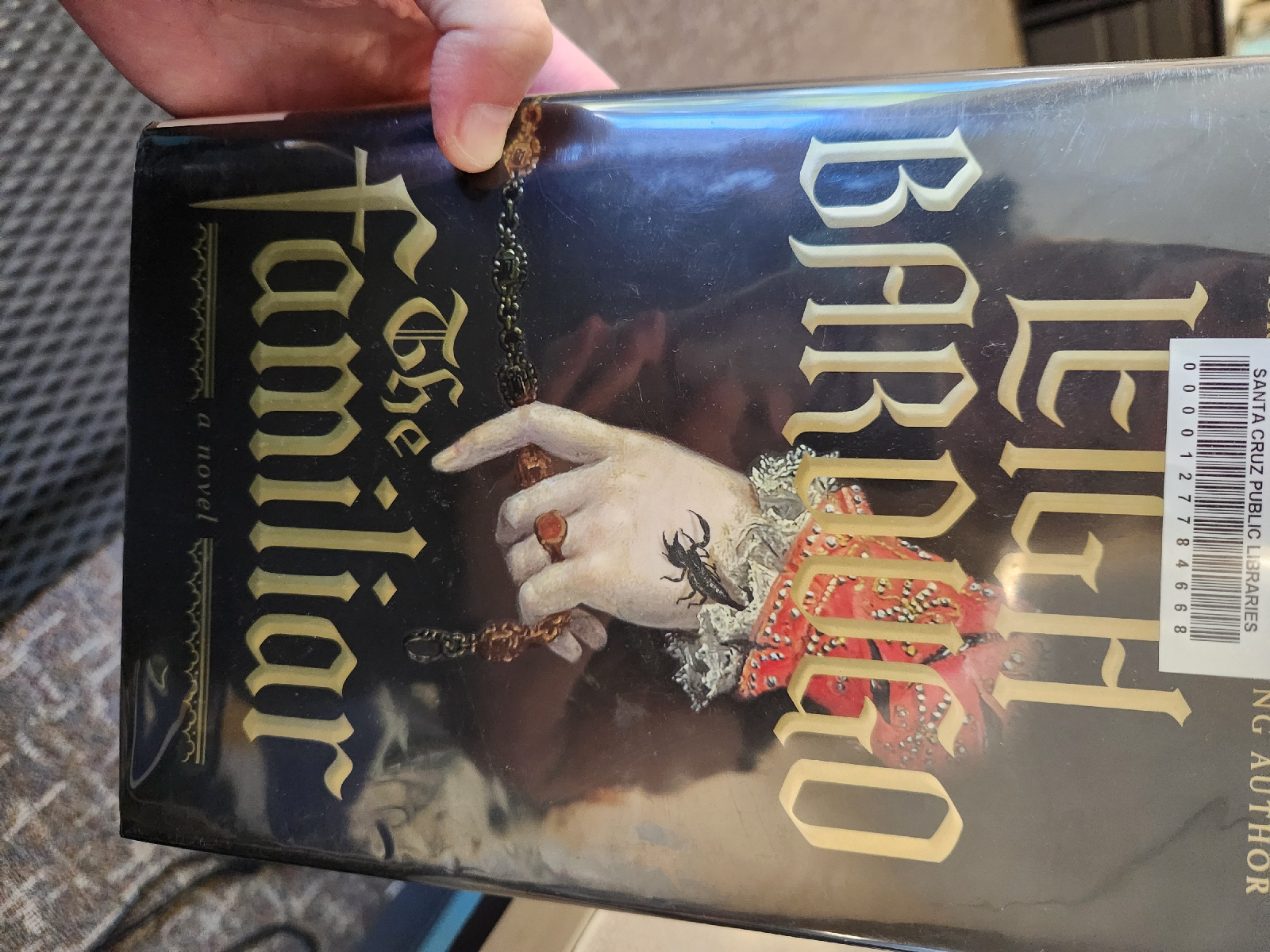

Archives and Manuscripts has been an eye-opening and fun class. I have really enjoyed the discussions, class sections, and coursework. This course was eye-opening because it pains me to admit, that I had a narrow view of what archivists do. My impression of them was simple and really only surface-level. I would often think about wanting to be an archivist and assuming that they just handled special collections. Now I know that there is so much more lurking below the title of Archivist. They are complex gatekeepers that facilitate the safety and security of knowledge. I did not know that they do not deal with collections on an item level and instead examine collections as a whole. On top of caring for collections, they must be discerning as to what is archived. They handle records after they have fulfilled their main purpose and make sure they would bring value to the institute collecting them. I also did not know the great deal at which they interact with researchers. That surprised me quite a bit. I did not think that they dealt with each other at all. I thought that once an item was archived, that was it. It was locked away. A part of me knew that researchers need collections to study but I just hadn’t thought about them in this way. But of course, there is a whole process for accessing records. The interactions between archivists and researchers, led me to reflect on a favorite series of mine, A Discovery of Witches. In the books (and TV Show) A Discovery of Witches, the main character Diana studies ancient texts and spends a lot of time in the Bodleian library. I found myself thinking about this a lot and realizing that there would have been a lot more safeguards up at the real Bodleian Library. The archivist on staff would have spent a lot of time talking with Diana about the books she wants to see. There would have been interviews and exit interviews. There is no way a book would have been misplaced as well. In the show, it looks as if almost anyone can come and go in the library. When in reality these collections would have been much more securely guarded. I do appreciate how the character Diana does handle the books with a cradle and seemingly wants to keep them safe as well. I watched a YouTube about the TV show set design and the set creators had to meticulously recreate the Bodleian library room, as the real library would not allow numerous guests, not to mention a television crew.

Archives and Manuscripts has been an eye-opening and fun class. I have really enjoyed the discussions, class sections, and coursework. This course was eye-opening because it pains me to admit, that I had a narrow view of what archivists do. My impression of them was simple and really only surface-level. I would often think about wanting to be an archivist and assuming that they just handled special collections. Now I know that there is so much more lurking below the title of Archivist. They are complex gatekeepers that facilitate the safety and security of knowledge. I did not know that they do not deal with collections on an item level and instead examine collections as a whole. On top of caring for collections, they must be discerning as to what is archived. They handle records after they have fulfilled their main purpose and make sure they would bring value to the institute collecting them. I also did not know the great deal at which they interact with researchers. That surprised me quite a bit. I did not think that they dealt with each other at all. I thought that once an item was archived, that was it. It was locked away. A part of me knew that researchers need collections to study but I just hadn’t thought about them in this way. But of course, there is a whole process for accessing records. The interactions between archivists and researchers, led me to reflect on a favorite series of mine, A Discovery of Witches. In the books (and TV Show) A Discovery of Witches, the main character Diana studies ancient texts and spends a lot of time in the Bodleian library. I found myself thinking about this a lot and realizing that there would have been a lot more safeguards up at the real Bodleian Library. The archivist on staff would have spent a lot of time talking with Diana about the books she wants to see. There would have been interviews and exit interviews. There is no way a book would have been misplaced as well. In the show, it looks as if almost anyone can come and go in the library. When in reality these collections would have been much more securely guarded. I do appreciate how the character Diana does handle the books with a cradle and seemingly wants to keep them safe as well. I watched a YouTube about the TV show set design and the set creators had to meticulously recreate the Bodleian library room, as the real library would not allow numerous guests, not to mention a television crew. Together they are a detailed photographic record of my life. Anyone could look at them and see events that happened and how I have grown. It is debatable if they are a true collection, however within the pictures are show tickets, cards, receipts, and other miscellaneous items. They showcase a big section of history and could be considered a personal record. I can see now that if there was a museum dedicated to me, they would be valuable, but right now they are only relevant to me. If CSUCI, the college I attended, wanted examples of life on campus, there are a few scrapbooks that would be of value to them. Their archivist would want those scrapbooks but not the rest of them.

Together they are a detailed photographic record of my life. Anyone could look at them and see events that happened and how I have grown. It is debatable if they are a true collection, however within the pictures are show tickets, cards, receipts, and other miscellaneous items. They showcase a big section of history and could be considered a personal record. I can see now that if there was a museum dedicated to me, they would be valuable, but right now they are only relevant to me. If CSUCI, the college I attended, wanted examples of life on campus, there are a few scrapbooks that would be of value to them. Their archivist would want those scrapbooks but not the rest of them.